I have a cough and a cold. I followed a recipe for home-made cough mixture. Cider vinegar, honey, ginger, cinnamon, Cayenne pepper. Potent, and rather delicious to someone who enjoys the tastes of vinegar and spices and sweetness. It evokes childhood memories of the silky black-brown Galloway’s cough syrup.

These remedies smell nice and feel like they are doing good. I have no evidence that they are more effective than cheaper and simpler alternatives. Honey and lemon and ginger is good, or just gargling with salt water.

My home-made cough mixture is a light muddy brown and I can see the spice particles floating around in the small ramekin dish. Perhaps if I add black treacle and put it in a dark glass medicine bottle, like Galloway’s, it would have a stronger placebo effect and appear more valuable.

Sellers of Snake Oil long ago touted their concoctions as effective remedies for anything, presumably asking a fortune for each little bottle, until the term became a by-word for a scam. We do not look kindly upon scammers.

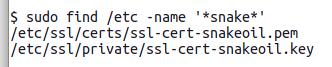

Recently I noticed a file named “snakeoil” on my computer. My suspicions were raised at first sight, but it is not a virus. It is a digital certificate created by the operating system. Let’s take a quick look at digital certificates and why this one is so named.

When our computer or smartphone retrieves a web page securely (the ‘s’ in ‘https’), it checks that the response came from the genuine server rather than some imposter trying to trick us. The way it knows is by asking the server to verify a digital certificate, a statement saying this server really belongs to this web address, signed by a digital signature. It requires a different specific response each time it asks, so that a rogue server cannot get away with playing back some response it learnt from the real server. Our software checks if the digital signature was made by someone that our software providers trust. If there is no signature, or it is invalid (for example past its expiry date, or names the wrong web address), or cannot be traced to someone our software provider trusts, then the browser raises a big warning that it may be unsafe to proceed. You might have seen the warning occasionally. Usually it is not an imposter trying to trick us but merely a missing or out of date certificate when the operator of a site has forgotten to update something properly.

These certificates for public servers are signed by well known authorities who have a track record of being trustworthy.

These certificates for public servers are signed by well known authorities who have a track record of being trustworthy.

What happens if I generate a certificate for myself, and sign it with a digital signature I just made up? This is legitimate and easy to do, and is called a self-signed certificate. If I set up my own server with this certificate, other people’s browsers won’t trust it. It can still be useful to me, though, if I intend to use it just from my own devices. I trust it, and when my browser shows a big warning I can tell my browser to “accept the risk and continue” or I can configure it to trust that certificate. Some companies set up servers this way for internal use, and developers regularly set up test servers this way.

If I try to convince members of the public to trust my self-signed certificate, however, I am like a snake oil salesman. “Look, user this server: its security certificate proves it belongs to google.com.” “Who are you kidding? That certificate is only signed by you. That proves nothing to me.”

The aptly named “snakeoil” file I came across is that self-signed certificate, provided for me so that I can use it for legitimate purposes if I want to. I just need to beware what it does and doesn’t prove.

I still have a cough. My little tub of Vicks VapoRub, another flashback to childhood, and the only one I have purchased in adulthood, no longer smells of anything to me today, having passed its use-by date just over ten years ago. I am pleased to find I can still buy a new tub of Vicks VapoRub for £4 at the supermarket. I wouldn’t mind some Galloway’s too, but apparently it has been discontinued.

Looking down Tesco’s long list of cold and cough remedies, one other product caught my eye, at £10 being the most expensive one sold. Covered in labels like “cold relief”, “congestion relief”, “nasal cleanse”, “super plus”, blah blah, it contains “all natural ingredients” and says a lot of pseudo-medical-sounding waffle about how gently and effectively it provides the exact kind of cleansing your nose needs. Then the punch line: this £10 bottle contains 135 ml of “100% pure sea water”. Worth every penny, I’m sure.